“I haven’t talked much about that day. The times were hard, and it brings up so many rotten emotions.”

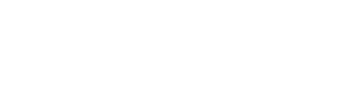

This month, History produced a documentary highlighting the attack on Pearl Harbor to pay tribute to the 75th anniversary of the “day of infamy.” To take part in that documentary, History producers contacted Pearl Harbor survivor Bob Glamm, a resident at CarDon & Associates’ Aspen Trace senior living community in Greenwood, Ind.

Born in 1918 in Chicago, Bob Glamm entered the world during the year of the Spanish Influenza, one of the worst plagues in history. He and his two sisters moved with their parents from Chicago to Freeport, Illinois, and then to the Milwaukee area, where most of his parents’ families were from.

Glamm lived much of his childhood in Wauwatosa, Wis., during the Great Depression, the longest-lasting and most widespread depression of the 20th century.

“As a child growing up during the Depression, meals were light and there were very few things to do for entertainment,” he said. “Other than playing out in the neighborhood with other kids, I had various paper routes that kept me busy. I also became interested in radio and had a little crystal radio set that received a couple different stations.”

Crystal radios were the first widely-used type of radio receiver, popular in the early days of radio. The earliest use of crystal radio was to receive Morse code radio signals transmitted by amateur radio operators. It was this interest that would serve Glamm later in life.

In 1935, he got his ham radio, or amateur radio, operator’s license. And at that time, the license required Morse code training for amateur operations. So Glamm learned Morse code — and became proficient.

“To get my license, I had to pass a strict test that I could only communicate in Morse code,” he said. A method of transmitting text information as tones, lights or clicks that can be understood only by the skilled listener, Morse code was “a lot of dots and dashes,” and not a lot of people had that expertise.

After graduating from high school in Wauwatosa, Glamm got a job with Western Electric, a job he called “the best, most, luckiest thing I ever did.” The electrical engineering and manufacturing company offered him stellar benefits and insurance — a company he stayed with until his retirement.

A few years after he started working at Western Electric, however, he received a letter from the Admiral at Great Lakes, home of the U.S. Navy’s only boot camp, located near North Chicago, Ill.

“The Admiral was searching for people who knew Morse code and were experienced in using it. He asked me if I wanted to see the world. I couldn’t turn him down,” Glamm said. “I knew the war was coming, and I knew I had experience that could help with communications. It was my honor to volunteer.”

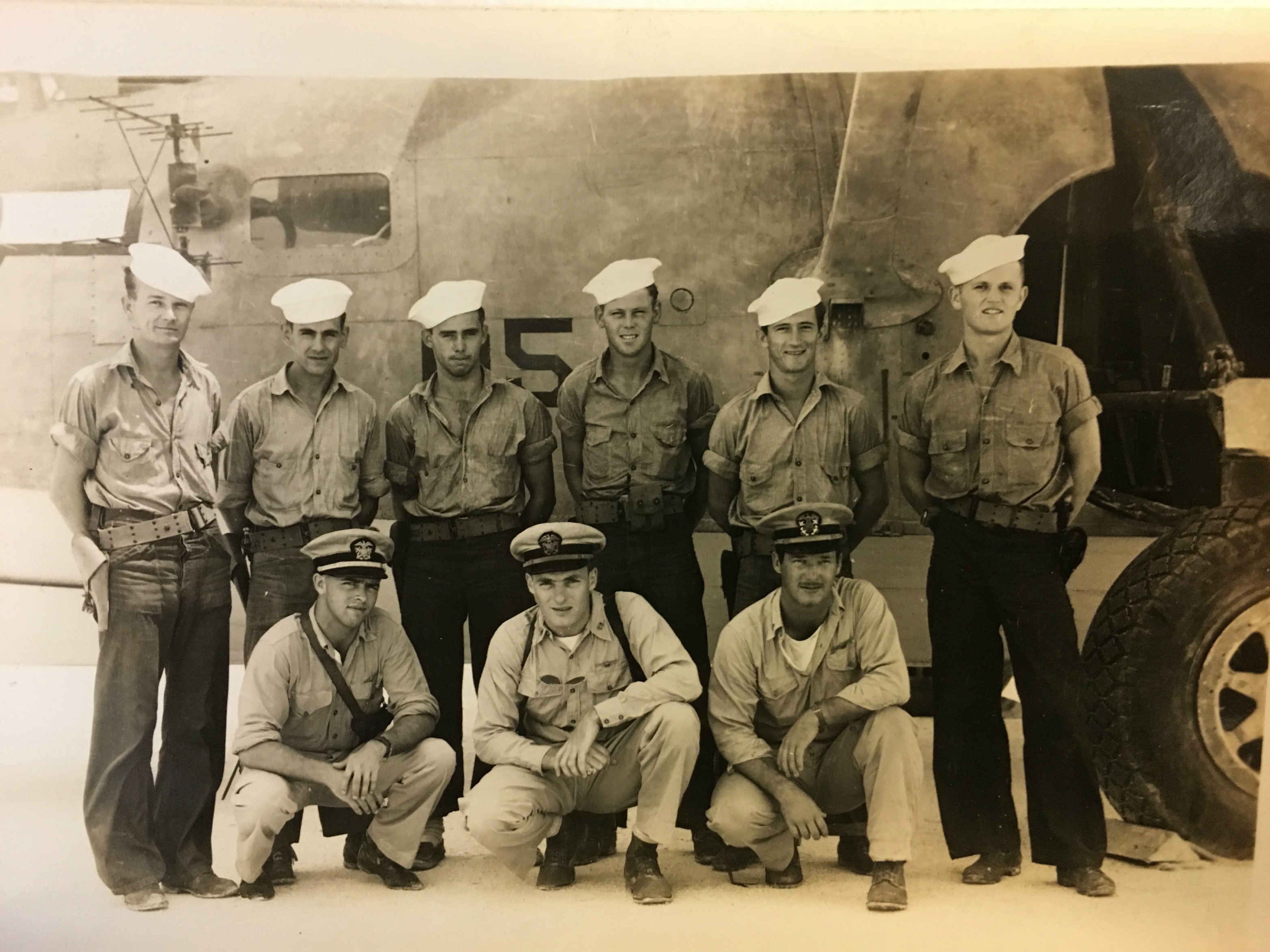

“Hallelujah,” he said. “Sure, at first it was a good assignment. The radio school was quite close, and I had various assignments with my squadron and flight crew, working my way up through the ranks.”

Then came the morning of Dec. 7, 1941.

“It was a Sunday morning. There were several artillery shots, and we heard the shells hit the ground. We were at first puzzled as to what was going on. There was all this noise, and I looked out the window and called out ‘It’s the Japs.’”

Glamm knew they were being attacked by the Japanese because he saw the rising sun flag on the side of the planes flying by, the symbol primarily used by the military forces of Imperial Japan and Japan’s Self Defense Forces.

“I got my best friend Willie, who was also a radio amateur, and we went down to the hangar,” Glamm said. “Halfway down, we saw a plane approaching us, and the pilot was obviously intent on doing damage. He did drop a small bomb, and we wound up with a skeleton of a hangar.”

Luckily, he survived. And soon after, the Admiral told Glamm to drive down to Battleship Row, the grouping of eight U.S. battleships in port at Pearl Harbor. Those ships bore the brunt of the Japanese attack that day.

“I’m at a loss for words how I felt,” he said. “I drove that truck down to where the battleships were at Ford Island and was told to start helping the sailors on one of the ships — one of the battleships that was sunk by a lucky strike.”

That ship was the U.S.S. Arizona — the flagship of Battleship Division One that suffered the worst damage and loss of life.

“It was just complete chaos. I was horrified to see all the destruction, but I had to follow orders. I continued to help rescue our sailors. But after that, things got quite hazy.”

In his early 20s, Glamm had experienced “going through hell being in the Armed Forces of the Navy that day.” The challenge after was how to put everything back together — how to learn from the attack that led the U.S. into World War II.

And while he was still serving in a reconnaissance role for the Navy during the war, Glamm married his childhood sweetheart during leave in 1943.

“My younger sister had a school chum who entwined herself throughout my heart, and we were married while I was in the service. I grew up with her, and we were married while I was on leave in San Diego. She and her mother took the train from Chicago so we could get married, and then they headed back.”

Glamm’s first son, David, was born in 1944, and when World War II ended in 1945, Glamm headed back to Wauwatosa and Western Electric.

He later decided to join the Army Reserve and served nearly 20 years before retiring as a First Sergeant. Glamm had already been through the attack on Pearl Harbor and World War II. Why would he then spend nearly two decades as part of the Army Reserve?

“Patriotism,” he said. Married to his childhood sweetheart, the Glamms had four children, two boys and two girls.

Glamm’s son David, also a veteran, said stories about Pearl Harbor never came easily from his dad.

“He became involved with the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association, which was cathartic for my dad and the other survivors,” he said. “They gathered to remember those fallen comrades and friends, and over time there was more conversation about what they saw — they realized it was history.”

Glamm took part in an interview for the documentary, “Pearl Harbor: 75 Years Later.” It explored the big stories and the lesser known details of what happened at Pearl Harbor, with accounts from experts, military minds and those who lived through it, like Glamm.

And to this day, Glamm still has the telegraph key he used that made him an instrumental piece in the Battle of Midway, a decisive battle between the U.S. and Japan shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor that proved irreparable for Japan and was considered a turning point in the Pacific War.

“The mission was to try to spot the Japanese fleet after Pearl Harbor, and my dad was in one of the PBYs flying in that mission,” David said. “They were ordered to fly under radio silence until someone spotted the Japanese fleet. The plane my dad was in saw them, and the aircraft pilot told my dad to signal they had been spotted. Dad alerted the entire Allied forces where the fleet was and where they were headed — sending the message in Morse code, and he still has that telegraph key today.”

Glamm possesses a unique historic artifact in his room at Aspen Trace — a telegraph key that became the key to giving a tremendous advantage to the Allied Forces in World War II.

Four kids. Seven grandkids. Twelve great-grandkids. A lifetime of lessons learned from one day in history that will never be forgotten. And Glamm has made more trips back to Pearl Harbor than he can count.

“I go to stand there and feel the wind on my face. There is such camaraderie with Pearl Harbor survivors. We go to both give thanks for our survival as well as pay homage to those we lost. We go to remember.”